This Sunday marks a turn in our Lenten journey; with the coming of the Fifth Sunday of Lent we now enter into the second part of this penitential season known as Passiontide. This time is marked by our use of the custom of veiling images in the Church, which not only mark a liturgical shift but also invites us to sharpen our focus.

This Sunday marks a turn in our Lenten journey; with the coming of the Fifth Sunday of Lent we now enter into the second part of this penitential season known as Passiontide. This time is marked by our use of the custom of veiling images in the Church, which not only mark a liturgical shift but also invites us to sharpen our focus.

The covering of these images, this “deprivation” of our sense of sight is meant to heighten our listening to the Word of God which will not focus on our Lord’s impending passion, death, and resurrection.

Even though we are making this liturgical shift into Passiontide this does not mean that we jettison the initial theme of Lent, the call to repentance and conversion, that has been guiding our journey since Ash Wednesday. This theme is manifested wonderfully in our Gospel this weekend with the story of the woman caught in adultery.

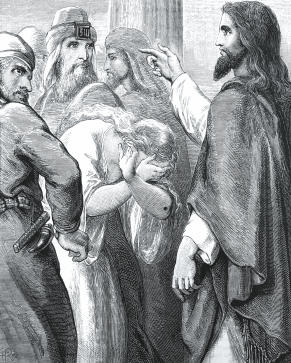

The Scribes and the Pharisees think they have finally caught the Lord. They bring a woman to him who has been caught in adultery (oddly, we hear nothing about the man even though adultery takes two people).

The Mosaic Law stated that such a crime was to be punished by stoning. If Jesus tells the crowd to let her go, then the authorities will say that he is subverting the law. If he tells them to follow the law and stone her, then the religious authorities can turn Jesus over to the civil authorities for inciting the crowd since the Jews could not inflict capital punishment on anyone themselves for any crime.

The Mosaic Law stated that such a crime was to be punished by stoning. If Jesus tells the crowd to let her go, then the authorities will say that he is subverting the law. If he tells them to follow the law and stone her, then the religious authorities can turn Jesus over to the civil authorities for inciting the crowd since the Jews could not inflict capital punishment on anyone themselves for any crime.

Next there is a rather dramatic pause, one that has baffled scholars as to what Jesus was writing on the ground. One theory, one which I very much like, says that the Lord was writing the sins of the woman’s would-be executioners on the ground in front of them. This theory is set forth because the normal Greek verb for “to write” is graphein; here, the Greek verb used is katagraphein which can mean “to write a charge against.” Whatever the Lord was doing in that moment is ultimately inconsequential because then he eloquently turns the tables on his would-be trappers. Reminding the crowd that the one who seeks to pass judgment is also liable to judgment, one by one they drop their stones and walk away.

The Gospel then leaves us with only the Lord and the woman, but to only focus on the Lord’s dispersing of the crowd and to not pay attention to the exchange that follows between the two would be a mistake. It would also be a mistake to underplay what the Lord says to her. The Lord Jesus extends his mercy to the woman, stating that he does not condemn her, but he also calls her to conversion: Go, and from now on do not sin anymore. Here we see the beautiful interplay between justice and mercy. Mercy is extended to this woman, but, with it, her conversion is commanded in justice. It is the same for us as well.

God does not dismiss our sins. He forgives us our sins with the understanding that we are to change our lives and avoid sin in the future.

Interestingly, this section of John’s Gospel was edited out for a time in the first few centuries of the Church’s life. St. Augustine states that this was done by certain Scripture scribes because it was a scandal to some in the early Church; a scandal that Jesus might seem to be “too light” on a sin as grievous as adultery. To the contrary of that ancient view of some, this story should be well-known to us because it reminds us first that, no matter how great our sinfulness may be, God’s love and mercy is greater. Second, as gracious as God’s forgiveness is, we should never be presumptuous of it, but accept it with humble gratitude and a firm resolve to change our lives. Finally, we must remember that ultimately there is one judge and no of us is he, and, in the end, we will all be in need of his mercy.

Father Christopher House is the Rector of the Cathedral and serves in various roles within the diocesan curia, namely Chancellor and Vicar Judicial.