Many of the world’s religions attest to the reality that something isn’t quite right with humanity. We see suffering and evil in our lives and the lives of others, often conceding to it as some unfortunate aspect of our existence that we can’t seem to do away with. We understand that it doesn’t fit into what life should be like. C.S. Lewis wrote about this in his apologetic work , Mere Christianity. He argued that humanity has always known there is something wrong with the world—the existence of evil and suffering—which clues us into something about the way the world should be. Lewis thought that if a line is crooked, how can we identify that it is indeed crooked unless we have a straight line with which to compare? In his analogy, the straight line reflects goodness and peace, whereas the crooked one, evil and suffering. We can only judge suffering and evil as undesirable if we have a desirable state with which to compare it.

Many of the world’s religions attest to the reality that something isn’t quite right with humanity. We see suffering and evil in our lives and the lives of others, often conceding to it as some unfortunate aspect of our existence that we can’t seem to do away with. We understand that it doesn’t fit into what life should be like. C.S. Lewis wrote about this in his apologetic work , Mere Christianity. He argued that humanity has always known there is something wrong with the world—the existence of evil and suffering—which clues us into something about the way the world should be. Lewis thought that if a line is crooked, how can we identify that it is indeed crooked unless we have a straight line with which to compare? In his analogy, the straight line reflects goodness and peace, whereas the crooked one, evil and suffering. We can only judge suffering and evil as undesirable if we have a desirable state with which to compare it.

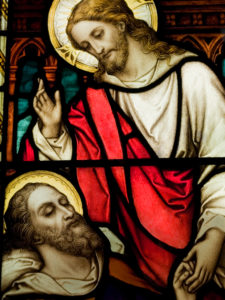

Christians talk often about the value—and unfortunate necessity—of suffering. Suffering is raw, telescoping our consciousness into our present pain, our state of helplessness. The saints suffered, and i f we read Scripture, we know that Jesus calls us to hoist up the cross on our shoulder—to trudge after him in a world that persecuted, beat, mocked and killed him. We know we are called to suffer, and to suffer sometimes without a satisfying explanation; but how do we endure? How do we carry the cross that leads to life, not the one that leads to death?

Suffering, in and of itself, is of no value. To suffer for the sake of suffering does not glorify God or bring about our sanctification. In some cases, it manifests a deep, dangerous pride that leaves no room for God’s grace.

In No Man Is An Island, Thomas Merton deeply contemplates the reality of suffering. Merton is quick, as many saints are, to speak of the necessity of suffering: its potential of edifying our souls and, when offered up with Christ’s ultimate act of sacrifice, of saving the souls of others. He echoes the wise words of the brilliant St. Augustine and mystical St. John of the Cross:

“Let us understand that God is a physician, and that suffering is a medicine for salvation, not a punishment for damnation.” (St. Augustine)

“Would that men might come at last to see that it is quite impossible to reach the thicket of the riches and wisdom of God except by first entering the thicket of much suffering, in such a way that the soul finds there its consolation and desire. The soul that longs for divine wisdom chooses first, and in truth, to enter the thicket of the cross.” (St. John of the Cross)

Yet, Merton also turns from a limiting focus on the benefits of suffering in the spiritual life, to its varied and ample pitfalls. For suffering, as we all know, can tempt us to rage against God and others—to cry out in a smoldering bitterness that can burn up our very souls. As Merton writes:

“Saints are not made saints merely by suffering. The Lord did not create suffering. Pain and death came into the world with the fall of man…[And so,] the Christian must not only accept suffering: he must make it holy. Nothing so easily becomes unholy as suffering.”

It’s human nature to believe that our own suffering is not only unique—which it is—but that it’s somehow greater than the suffering of others. When we don’t have the power to remove our suffering, we are left with only a choice: how we respond to it. It can be easy to lament that no one understands how difficult our trials, judging our warring interior with the seemingly pleasant exterior of others. As a result, we can become angry with God, accusing him of dealing with us unfairly. We may falsely craft the illusion that we are not pleasing to God because of his perceived punishment—believing God deals with us harshly because we are less loved by him, his ingrate children that he merely puts up with.

Of course, we can also plummet into the opposite line of thinking, supposing that our own unique suffering makes us better and more loved than others. If God’s gift of suffering invites us into a greater closeness with his Paschal Mystery—which it can—then our ego can be tempted to sink its teeth firmly into the tender meat of pride. Here we can mistakenly pick up crosses that have not been left for us by Christ.

Of course, we can also plummet into the opposite line of thinking, supposing that our own unique suffering makes us better and more loved than others. If God’s gift of suffering invites us into a greater closeness with his Paschal Mystery—which it can—then our ego can be tempted to sink its teeth firmly into the tender meat of pride. Here we can mistakenly pick up crosses that have not been left for us by Christ.

“Actually, the only sufferings anyone can validly desire are those precise, particular trials that are demanded of us in the designs of Divine Providence for our own lives.” (Thomas Merton)

We see some of the ways we are not called to suffer, yet again we must ask: How do we suffer well—in the way Christ calls us to?

We would do well to eschew the belief that we can ameliorate all suffering in this life through technology, modern innovations, medicine and a general capacity for human beings to transcend to a state bereft of any suffering. Of course, we do believe in the existence of this state—we call it heaven, or the Kingdom of God —but we must always remember God can only usher it in. We are incapable of remedying our own suffering completely. There is a level of peace that comes with accepting that our lives will always entail a certain degree of toil and difficulty. I’ve always been encouraged by the apocryphal words of St. Teresa, that even the greatest suffering in this life, when compared to the infinite joy and ecstasy of heaven, “is like a bad night in a bad inn.”

At the same time, we’re called to do as Jesus did: heal the sick, comfort the lonely, ease humanity’s collective burden by being sacraments of his love. And this includes easing our own suffering so that it does not prove a spiritual snare. We should reach out to others in our suffering so that they have the opportunity to become a sign o f Christ’s merciful love. Christ gave his hands, feet, and heart to the Church, and after we take advantage of the grace that’s offered in prayer and the sacraments, we must seek his healing through others. Christ didn’t heal those who were sick; he healed those who were sick and asked to be healed. We must ask God, as well as our brothers and sisters, to comfort and help us in our suffering.

“Jesus who cannot suffer long to keep you in affliction will come to relieve and comfort you by infusing fresh courage into your soul.” (St. Padre Pio of Pietrelcina)

However, as much as God and others can relieve our suffering, we all know there will still be times when we’re left to our own pain—when it’s inescapable despite our prayers, the sacraments, and the mercy of others. In those moments, we are left with the choice to allow it to not only sanctify us, but others as well. This is a great gift that God gave to us by his suffering— by his sanctification of human suffering on the cross—that he enables us to join our suffering with him to help save the souls of others. We choose to suffer well as an act of love for God and others. And so we are never left to suffer without purpose or meaning as long as it’s ordered rightly to Christ. As soon as we allow our suffering to becomes meaningless, not in any way connected to our own sanctification or the salvation of others, then it becomes void and vacant—and that is never God’s will for us. Our suffering alone doesn’t save us; it points instead to Christ’s suffering that does.

“To know the Cross is not merely to know our own sufferings. For the Cross is the sign of salvation, and no man is saved by his own sufferings. To know the Cross is to know that we are saved by the sufferings of Christ; more, it is to know the love of Christ Who underwent suffering and death in order to save us…In order to suffer without hate we must drive out bitterness from our heart by loving Jesus.” (Thomas Merton)

When a season of suffering overcomes us and leaves us on our knees, there is no intellectual explanation or clever bit of insight that will take away our pain. And at times there is no one person who can console our yearning, troubled soul. But we have Jesus, our God. And we can clutch onto his cross, look into his sorrowful eyes, and know that we are not alone. We can know that the God who suffers—ever loving and always compassionate—also suffers with us.

“The Son of God suffered unto the death, not that men might not suffer, but that their sufferings might be like His.” (George MacDonald)

Chris is the founder of The Call Collective, a blog exploring the intersection between faith, culture and creativity. He holds bachelors’ degrees in English and Economics from UCLA and currently works as a Lead Content Strategist for Point Loma Nazarene University.