The question has been put to me again and again. Ever since the stories of child sex abuse broke out of Boston in 2002 and threw the Catholic Church headlong into an ongoing and painful Lent, people have asked me: “Why are you still a Catholic?”

The question has been put to me again and again. Ever since the stories of child sex abuse broke out of Boston in 2002 and threw the Catholic Church headlong into an ongoing and painful Lent, people have asked me: “Why are you still a Catholic?”

Over the course of this summer, in the wake of revelations about former Cardinal Theodore McCarrick’s criminal abuse of minors and his longstanding sexual exploitation of seminarians, the soulshattering Grand Jury report out of Pennsylvania, and the ugly, repellently partisan sniping among Catholics (both clerical and lay) over the controversial and still-unresolved testimonio of a former papal nuncio to the United States, the question has been asked more frequently and with growing urgency: “Why are you still part of this Church, so beset by ecclesial politics, run by so many feckless leaders, so saturated with a mindset of secrecy as to hide acts of real evil perpetrated against innocence? How do you maintain your faith amid so much darkness?”

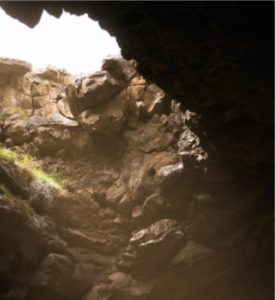

Well, when have darkness and light been anything but co-existent? How do we recognize either without the other?

I remain within the Catholic Church because it is a Church that has lived and wrestled within the mystery of the shadowlands ever since an innocent man was arrested, sentenced, and crucified, while the keeper of “the keys” denied him, and his first priests ran away. Through two thousand imperfect years—sometimes glorious, sometimes heinous—the Church has contemplated and manifested the truth that dark and light, innocence and guilt, justice and injustice all move together, back and forth like wind-stirred wheat in a field, churning toward a culmination imaginable yet out of reach.

I remain within the Catholic Church because it is a Church that has lived and wrestled within the mystery of the shadowlands ever since an innocent man was arrested, sentenced, and crucified, while the keeper of “the keys” denied him, and his first priests ran away. Through two thousand imperfect years—sometimes glorious, sometimes heinous—the Church has contemplated and manifested the truth that dark and light, innocence and guilt, justice and injustice all move together, back and forth like wind-stirred wheat in a field, churning toward a culmination imaginable yet out of reach.

Yes, in a Church of billions, a number of her clergy have sinned, and gravely—criminally—against too many. If this darkness were her only reality, how could I remain?

But the other reality is one of light—the light that shines through the service of innumerable priests, religious, and layfolk who have faithfully labored in the fields of the Lord and honored his creation, and his creatures, by offering him the best of their energies. I read of the Passionist priest Father Rick Frechette building hospitals in Haiti and burying her dead, and I see light.

I meet Sacred Heart of Jesus Sister Rosemary Nyirumbe and see how her mission to teach one skill has saved the lives of thousands of exploited people touched by evil, and I see light.

Both Father Rick and Sister Rosemary shine with it, as do the Benedictines of Mary, the old-school Benedictine nuns who are building an abbey, one psalm and one song at a time, in order to give worship and praise to God on our behalf—to pray day and night for those of us who cannot or will not pray—for the sake of the whole world.

So do the thousands of volunteers who assist the poor through the St. Vincent de Paul Society or the Knights of Columbus. So do the anonymous people in our parishes, who work the outreach, light the candles, knit the prayer shawls, visit the sick, teach the young, or shovel the walkway after a snowstorm. All of it helps to illumine the dark, brighten the light.

And then, of course, there is the brightness of the Holy Eucharist, the incomparable Bread of Life, supersubstantial and luminescent. To be before it is to know, “Yours is more than mortal beauty; every word you speak is full of grace.”

If the Church is a paradox of light and dark, that is really not so unusual, is it? Consider our nation: we are a “beacon of freedom” but formed by men who owned slaves. We are a nation of demonstrated goodwill and generosity—quick to send aid to others in the face of natural disasters—yet also the only nation that has ever deployed a nuclear weapon of mass destruction.

Consider the darkness and light that resides within ourselves too. I am a woman with very generous instincts, and I try to love everyone, but I am capable of corrosive scorn. Have I been much sinned against? Yes. So have you. Have I sinned against others? Oh, yes. So have you.

Like a pebble cast into a pond, our every action ripples out toward the edges, reaching farther than we intended, touching what we do not even know, for good and for ill. It all either means nothing, or it means everything.

As a Catholic, I believe it means everything.

That doesn’t mean I do not suffer for the sins of my Church; we people in the pews are roiling with feelings of betrayal, shame, revulsion. My stomach aches with it; I am sometimes sleepless and edgy, and wondering what will happen next.

But I will remain, because on the other side of this darkness I see the light that is faith working within me, and many others, specifically due to this crisis. I have dug in my heels for the sake of this Church and her people, so I am also praying more for the victims and for all of us; for the Truth to triumph, for Wisdom to reign. I am fasting more, and being quicker to “offer it up” when pain or anxiety arises. I am “working my faith” in a new and more mindful way than I have in a long time, and I know I am not alone in any of it. I see light in the determined faith of other Catholics.

Having survived sexual abuse in the family and the public schools, I identify deeply with the pain, the sense of powerlessness and abandonment that the victims of some of our priests and leadership have endured. I grieve for them—and for my Church, and for all of the countless good priests and religious who are tarnished by the actions of a depraved minority.

I am saddened beyond words to know that the Church’s sins of commission and omission are casting doubt into the hearts and minds of many, and that some are leaving. They will miss the consolations of the Church in light, out of understandable concern for its shadows.

Finally, I see light in the crucifix. There, on the wood of the cross, we encounter Jesus, son of Mary, who knew shame, betrayal, abandonment, scorn, jeering, ridicule, unimaginable pain and sorrow, and submitted to them in order to draw us into a consoling embrace that says, “I know what you are feeling; I know what you are thinking. You tortured ones, you shamed ones, you innocent ones, you slandered ones; I am the One who knows, and we are actually all in this together, and quite outside of time.”

The darkness within my Church is real, and it has too often gone unaddressed. That absolutely must change.

I will do my part, because I want my Church to shine. But I understand that everything, from our institutions to our innermost beings, are now seen only as through a glass, darkly. Arms outstretched, listening for the Word and its echoing liturgy, I make my way forward, in bright hope.

Elizabeth Scalia is a Benedictine Oblate and author of several books including the award-winning Strange Gods: Unmasking the Idols in Everyday Life (Ave Maria Press) and Little Sins Mean a Lot (OSV). Her work can be found on the Word on Fire Blog and is used with permission.