Feast Day: August 11th

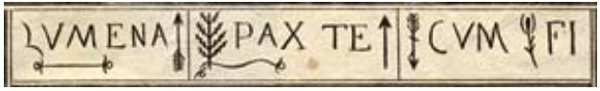

Let us begin by heading to Rome on May 25th, 1802. In the wider world, we are shortly after Napoleon’s concordat with Pius VII (in 1801, allowing Catholicism to be practiced again in France) and shortly before the same Napoleon sold the Louisiana territory to Thomas Jefferson (in 1803, doubling the landmass of our country). We step down into one of the most ancient, and most revered, of the catacombs, that named after St. Pricilla, North and West of the ancient city where the bones of several early popes and our friends St. Praxedes and St. Pudentiana were all buried before being reinterred elsewhere in the 900s. A group of workers are working in the old and empty tunnels and erupt in excited shouts: there is a small shelf-grave that appeared unopened. Sure enough, behind a set of three tiles inscribed with the ancient letters “LUMENA PAX TE CUM FI” and symbols of arrows, a lance, anchor, and lily (or flame), were found the bones of a teenage girl, her skull fractured, and a glass vial with the residue of what appeared to be blood.

Archeologists are fairly certain that the bones are those of a young maiden, though the vial and head injury are not certain indicators of martyrdom (though that assumption is a sensible one). The letters and symbols do indicate that this is a tomb from the second century, BUT (crucially), the tiles are actually in the wrong order. They should read “Pax te cum Filumena” (“Peace be with you Philomena”), and with the way they are written, we can tell that the reason they are out of order is because at some point they were taken off (a different?) grave and placed over this one.

In any case, the relics were translated a few years later (June 8th, 1805) to the church of Mungano (near Naples), and later (in 1827) that church was given the earthen tiles with the inscription as well. People began to visit the shrine of the little saint and reports of miracles quickly grew. Popular accounts record that a 10 year old boy, crippled and unable to walk, stood up during the consecration of one of the Masses celebrated in the octave after Philomena’s relics were brought to Mungano. On the same day, during vespers, a two year old little girl, blind from smallpox, received her eyesight after her mother put some of the oil from the lamp above Philomena’s tomb on her eyes. And then a man who did not believe, seeing the miracle, spontaneously received the gift of faith and offered to fund the construction of a chapel to the martyr! More certified accounts record a lawyer from Naples, D. Alessandro Serio, who suffering from an internal illness came to Philomena’s tomb in 1814 hoping for a cure. The illness actually grew markedly worse and he seemed to be on the brink of death, and worse, was incapacitated to such an extent that he could not make a good confession. His wife, still asking for Philomena’s intercession, brought a picture of the saint to him, begging that at least he would recover enough to receive the last sacraments. His pain disappeared and the disease with it.

The account of these and other miracles led the Congregation of Rites in 1834, to approve Philomena’s veneration during Mass in the region around Mungano. Pope Gregory XVI confirmed (on January 30, 1837) that preliminary permission after having met the paralyzed, and desperately ill, Pauline Jaricot, who returned to Rome after her visit to Philomena’s tomb in 1834 entirely cured. She it was who carried a relic of Philomena back to her home country of France and gave it to a certain Curé de Ars, who was said to have converses with the martyred saint in his prayer, and who routinely credited St. Philomena with marvelous cures of his own health and others (this also handily kept that attention from being given to himself!)

But here’s the hard truth that this whole story gives to us as well. August 11th was only ever a local feast-day for Philomena. And the possibility of her martyrdom, and all these miracles, and the saints and mystics who loved and spoke so highly of their little “Lover of Light” (as Philomena’s name means), are not the same as canonization. Canonization is an infallible proclamation by the Pope that someone is in heaven, a saint before God whom we can all ask their intercession. No Pope has ever infallibly declared such about the young woman who was buried in the catacombs of Pricilla. In fact, on January 30th, 1961, Pope St. John XXIII decided to remove St. Philomena from even the local calendars where she had been venerated. That doesn’t mean she’s not a saint, it just means that the Church has not done the careful work to verify the miracles attributed to her (and, considering that saints are canonized also to hold their lives up for our veneration; with no solid historical details of Philomena’s life, it is unlikely that she could be formally canonized.)

– Fr. Dominic is just as disappointed as any of you by this (and other places where the Church’s slowness and caution challenges my own devotions). But here’s a key lesson for all of us: Healings are real whether proven or not. Saints are in heaven whether canonized or not. BUT ALSO, no devotion or personal affection should trump our fidelity to Christ’s Body, the Church, and Christ’s vicar, our Holy Father. Docility to the Church’s way of praying are higher goods than my own pious preferences!