Stewardship of Time & Talent

Time in prayer is a great practice for discerning your talents and what you may be able to share with the Parish!

Stewardship of Treasure

Weekly Collections: May 5th & 6th

Envelopes: $6,762.00

Loose: $3,430.29

Maintenance: $2,009.00

__________________________

TOTAL: $12,201.29

Needed to operate weekly: $15,907.89

Difference: $3,706.60

April EFT: $18,486.10

These are recurring electronic donations over the month.

We are adding a new section to the Weekly in the coming weeks. To celebrate our community and to get to know each other better, we are creating a section in the weekly that highlights parishioner news, prayer requests, and sacramental news to share.

We are adding a new section to the Weekly in the coming weeks. To celebrate our community and to get to know each other better, we are creating a section in the weekly that highlights parishioner news, prayer requests, and sacramental news to share. Many of the world’s religions attest to the reality that something isn’t quite right with humanity. We see suffering and evil in our lives and the lives of others, often conceding to it as some unfortunate aspect of our existence that we can’t seem to do away with. We understand that it doesn’t fit into what life should be like. C.S. Lewis wrote about this in his apologetic work , Mere Christianity. He argued that humanity has always known there is something wrong with the world—the existence of evil and suffering—which clues us into something about the way the world should be. Lewis thought that if a line is crooked, how can we identify that it is indeed crooked unless we have a straight line with which to compare? In his analogy, the straight line reflects goodness and peace, whereas the crooked one, evil and suffering. We can only judge suffering and evil as undesirable if we have a desirable state with which to compare it.

Many of the world’s religions attest to the reality that something isn’t quite right with humanity. We see suffering and evil in our lives and the lives of others, often conceding to it as some unfortunate aspect of our existence that we can’t seem to do away with. We understand that it doesn’t fit into what life should be like. C.S. Lewis wrote about this in his apologetic work , Mere Christianity. He argued that humanity has always known there is something wrong with the world—the existence of evil and suffering—which clues us into something about the way the world should be. Lewis thought that if a line is crooked, how can we identify that it is indeed crooked unless we have a straight line with which to compare? In his analogy, the straight line reflects goodness and peace, whereas the crooked one, evil and suffering. We can only judge suffering and evil as undesirable if we have a desirable state with which to compare it.

Of course, we can also plummet into the opposite line of thinking, supposing that our own unique suffering makes us better and more loved than others. If God’s gift of suffering invites us into a greater closeness with his Paschal Mystery—which it can—then our ego can be tempted to sink its teeth firmly into the tender meat of pride. Here we can mistakenly pick up crosses that have not been left for us by Christ.

Of course, we can also plummet into the opposite line of thinking, supposing that our own unique suffering makes us better and more loved than others. If God’s gift of suffering invites us into a greater closeness with his Paschal Mystery—which it can—then our ego can be tempted to sink its teeth firmly into the tender meat of pride. Here we can mistakenly pick up crosses that have not been left for us by Christ.

Here’s a great discipleship opportunity!

Here’s a great discipleship opportunity! You can: Call me at the Cathedral. My extension is 132. Email me at

You can: Call me at the Cathedral. My extension is 132. Email me at  “Be excellent to each other” is not only the catch-phrase of an 80s cult classic but also an excellent guide to life. And despite its dubious origin, there is wisdom contained in the memorable phrase, a wisdom of which we might need reminding.

“Be excellent to each other” is not only the catch-phrase of an 80s cult classic but also an excellent guide to life. And despite its dubious origin, there is wisdom contained in the memorable phrase, a wisdom of which we might need reminding. “Bring flowers the fairest, bring flowers the rarest, from garden and woodland and hillside and dale; our full hearts are swelling, our glad voices telling the praise of the loveliest flower of the vale!”

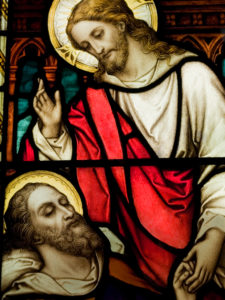

“Bring flowers the fairest, bring flowers the rarest, from garden and woodland and hillside and dale; our full hearts are swelling, our glad voices telling the praise of the loveliest flower of the vale!” During this month of May, as we continue our celebration of the Easter season and the new life won for us by the risen Christ, we are mindful again of the role that Mary played in the drama of our salvation. God’s plan for our salvation in his son Jesus began with Mary’s yes to God’s will for her. We are invited daily to echo Mary’s yes to God’s will in our lives because salvation is the ultimate end of God’s will for each and every person. We honor Mary throughout the Church year, but particularly in this month, because she is our great model of discipleship and our great intercessor with Jesus her son.

During this month of May, as we continue our celebration of the Easter season and the new life won for us by the risen Christ, we are mindful again of the role that Mary played in the drama of our salvation. God’s plan for our salvation in his son Jesus began with Mary’s yes to God’s will for her. We are invited daily to echo Mary’s yes to God’s will in our lives because salvation is the ultimate end of God’s will for each and every person. We honor Mary throughout the Church year, but particularly in this month, because she is our great model of discipleship and our great intercessor with Jesus her son. Every month , the International Catholic Stewardship Council writes about a Saint who lived a stewardship way of life. We will begin to share these examples each month, so we too can lear how to bear witness to the Gospel in our lives. For more information,

Every month , the International Catholic Stewardship Council writes about a Saint who lived a stewardship way of life. We will begin to share these examples each month, so we too can lear how to bear witness to the Gospel in our lives. For more information,