In my prayer life, I am an exhaustor of options. I wish this meant that I spent hours in contemplation, examining my needs and God’s responses as if marveling at a diamond under a magnifying glass. What it really means is that God is often the last place I bring my fear and worry.

My anxieties first get stuffed away. I minimize and hide them, frustrated that they have once again appeared. When that doesn’t work (it never does), I analyze. I put them to paper, turn them over in my mind, and attempt to calculate their causes and cures on my own. I do this because I fear that God’s attention is finite. If I can only go to him once, my thinking goes, I had better make sure I get the “ask” right. I have a hard time remembering that God wants it all, that I can bring him the mess without first attempting to clean it up on my own.

This methodical and measured approach to comfort-seeking is contrasted by the impulsivity of my 2- year-old son. His cries immediately and urgently ring out, when he is hungry or tired, when he wants help or sympathy, and sometimes for no clear reason at all. Every need, large or small, is loudly and instantly expressed. His demands are exclaimed with the confidence that someone is hearing and receiving, pleas and prayers of their own right.

And out of my infinite love for him, I respond with equal urgency. I place his bicycle back upright on the sidewalk, I retrieve the book he is reaching for, or repeat for the third time that dinner is almost ready. In these moments, I surprise myself with my patience and tenderness. And I wonder, if the human response to these cries is so immediate and attentive, how much stronger and more vast, must the instinct to comfort be for God?

In observing my toddler, I notice what is often missing in my grown-up prayers: a single, instinctual cry. I too often rationalize and reason, dissecting my worry and fear into more manageable pieces before it ever goes to God. When I found myself recently overwhelmed with balancing responsibilities of work and home during this time of quarantine, I parsed out to-do lists and turned to them wildly, looking to control whatever I could. I filled any time I might have had for being with doing, unable to separate out the symptoms of anxiety from their cause and therefore reticent about bringing them to prayer. The impulsiveness of a child buried within, a direct line to the almighty kinked by “shoulds” and “not yets.” This mess, I reasoned, was not yet worthy of God; mine was a thread too twisted and tangled for him to unknot.

We learn to temper and modulate emotion as we age, and this serves us in many instances. Yet the instinct to cry out is still wired within us. We are still those little people, somewhere deep in there. And when we struggle in prayer, I suspect it is those little people God simply wants to hear from. Just as a parent immediately responds to a young child calling for “Mama,” God only needs to hear the call “Abba,” the most tender “Daddy,” to summon his full attention, grace, and love. It is with these simple cries that we humble ourselves and by doing so, grow ever closer to Christ.

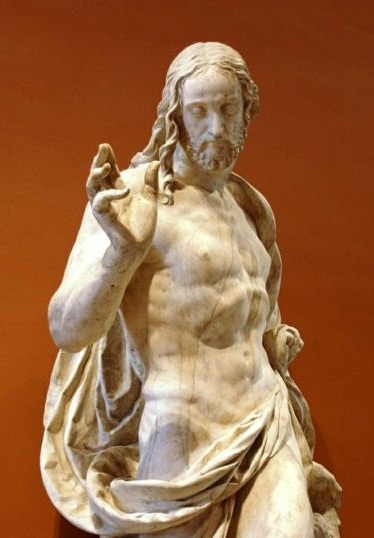

I often think of Jesus’ most poignant cry on the cross, visiting this moment as one of the rawest we see in Scripture. “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” he cries out. This scene presents in full color, Jesus as man, and simultaneously gives us a model of uninhibited, guttural, instinctual prayer. A holy and productive cry, not unlike the hourly cries of a child. His is a prayer that is immediately and urgently human, and in a language we sometimes forget that God understands.

This Easter Season, particularly with the weight of our world’s current crisis, how are we orienting ourselves as children of God and embracing the humility that comes with it? How can we reconnect with our ability to cry out? And when we sit in that gutwrenching moment on Good Friday, how are we modeling our prayer after Jesus’ own cry long past Easter Sunday?

Christina Ferguson is a nonprofit and corporate senior manager, writer, and mother. Currently serving at Graham-Pelton, Christina has worked with Leadership Roundtable, Georgetown University, Catholic Relief Services, and Ashoka: Innovators for the Public. She holds a Master’s Degree in Public Policy from Georgetown University and a Bachelor’s of Science in Finance from Villanova University.

This Sunday concludes the Octave of Easter. An octave is a celebration of eight days in the Church and each day is honored liturgically in the same way as the day in which the octave began, in this case Easter Sunday. Following the reforms of Vatican II, only two octaves remain in the ordinary form of the Churches liturgical calendar: Easter and Christmas. While the octave may be finishing, the joy of the Easter Season continues on. This was a Triduum unlike any other. The liturgies were beautiful and I am grateful for the comments that we received from folks via social media. While they were beautiful, they were lacking in that you were not able to be there and that subdued the joy that naturally comes from the celebration of Easter. I wish to thank our own Mark Gifford for providing us with the beauty of the organ during our celebrations, thank you to Andrew Hansen and Michael Hoerner from the Catholic Pastoral Center for filming/streaming our celebrations, and thank you to my confreres in the clergy and our seminarians for helping to make the liturgies happen.

This Sunday concludes the Octave of Easter. An octave is a celebration of eight days in the Church and each day is honored liturgically in the same way as the day in which the octave began, in this case Easter Sunday. Following the reforms of Vatican II, only two octaves remain in the ordinary form of the Churches liturgical calendar: Easter and Christmas. While the octave may be finishing, the joy of the Easter Season continues on. This was a Triduum unlike any other. The liturgies were beautiful and I am grateful for the comments that we received from folks via social media. While they were beautiful, they were lacking in that you were not able to be there and that subdued the joy that naturally comes from the celebration of Easter. I wish to thank our own Mark Gifford for providing us with the beauty of the organ during our celebrations, thank you to Andrew Hansen and Michael Hoerner from the Catholic Pastoral Center for filming/streaming our celebrations, and thank you to my confreres in the clergy and our seminarians for helping to make the liturgies happen.

It looks like many of us will be spending more time at home for a few weeks, whether for selfquarantine, lockdown, or social distancing. What can we do to keep ourselves spiritually engaged and even grow during this time, rather than stagnate or fall away from our spiritual disciplines? Here are a few suggestions.

It looks like many of us will be spending more time at home for a few weeks, whether for selfquarantine, lockdown, or social distancing. What can we do to keep ourselves spiritually engaged and even grow during this time, rather than stagnate or fall away from our spiritual disciplines? Here are a few suggestions.

Such is the case with Thomas and the other apostles in today’s gospel. They had set all their hope on Jesus. And it all came to a horrifying and humiliating end with the crucifixion. Now, they were reduced to hiding behind a locked door for fear that the authorities would do to them what they had done to Jesus.

Such is the case with Thomas and the other apostles in today’s gospel. They had set all their hope on Jesus. And it all came to a horrifying and humiliating end with the crucifixion. Now, they were reduced to hiding behind a locked door for fear that the authorities would do to them what they had done to Jesus. On behalf of Bishop Paprocki and the Cathedral clergy and staff, I pray that the Lord will bless you and yours this Easter with the fullness of His grace and the joy that comes from Him alone. With every cross may we remember that the cross is never an end unto itself. In moments of sacrifice and desolation may we know that we are not alone or forsaken. May we always be mindful that Easter teaches us that God always gets the last word, and in the case of the cross and the tomb, His last word is life. All honor, praise, and glory to the risen Christ, who, by His death and resurrection, has gained for us the rewards of everlasting life! Happy Easter (and I hope to be able to wish that in person at some point during the fifty days of this holy season)!

On behalf of Bishop Paprocki and the Cathedral clergy and staff, I pray that the Lord will bless you and yours this Easter with the fullness of His grace and the joy that comes from Him alone. With every cross may we remember that the cross is never an end unto itself. In moments of sacrifice and desolation may we know that we are not alone or forsaken. May we always be mindful that Easter teaches us that God always gets the last word, and in the case of the cross and the tomb, His last word is life. All honor, praise, and glory to the risen Christ, who, by His death and resurrection, has gained for us the rewards of everlasting life! Happy Easter (and I hope to be able to wish that in person at some point during the fifty days of this holy season)!

This ancient hymn, the Victimae Paschali Laudes, is one of only a few “sequences” still in use in the Catholic Church today. A sequence— for your Catholic trivia file—is a hymn traditionally sung just before the Gospel proclamation. Before the reforms of the Mass in 1570, there were many such hymns on feast days and solemnities throughout the Church year. The current Roman Missal has only three: the above sequence for Easter, the Veni Sancte Spiritus for Pentecost, and the recommended (i.e. optional) Lauda Sion for the Solemnity of Corpus Christi.

This ancient hymn, the Victimae Paschali Laudes, is one of only a few “sequences” still in use in the Catholic Church today. A sequence— for your Catholic trivia file—is a hymn traditionally sung just before the Gospel proclamation. Before the reforms of the Mass in 1570, there were many such hymns on feast days and solemnities throughout the Church year. The current Roman Missal has only three: the above sequence for Easter, the Veni Sancte Spiritus for Pentecost, and the recommended (i.e. optional) Lauda Sion for the Solemnity of Corpus Christi.