Lenten Journey for Saturday of the fourth week of Lent

A Scandalous Mercy

This Sunday marks a turn in our Lenten journey; with the coming of the Fifth Sunday of Lent we now enter into the second part of this penitential season known as Passiontide. This time is marked by our use of the custom of veiling images in the Church, which not only mark a liturgical shift but also invites us to sharpen our focus.

This Sunday marks a turn in our Lenten journey; with the coming of the Fifth Sunday of Lent we now enter into the second part of this penitential season known as Passiontide. This time is marked by our use of the custom of veiling images in the Church, which not only mark a liturgical shift but also invites us to sharpen our focus.

The covering of these images, this “deprivation” of our sense of sight is meant to heighten our listening to the Word of God which will not focus on our Lord’s impending passion, death, and resurrection.

Even though we are making this liturgical shift into Passiontide this does not mean that we jettison the initial theme of Lent, the call to repentance and conversion, that has been guiding our journey since Ash Wednesday. This theme is manifested wonderfully in our Gospel this weekend with the story of the woman caught in adultery.

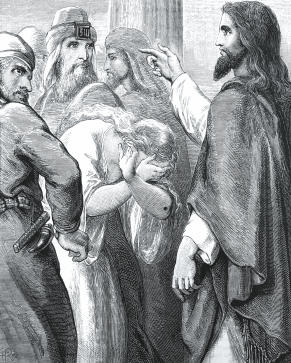

The Scribes and the Pharisees think they have finally caught the Lord. They bring a woman to him who has been caught in adultery (oddly, we hear nothing about the man even though adultery takes two people).

The Mosaic Law stated that such a crime was to be punished by stoning. If Jesus tells the crowd to let her go, then the authorities will say that he is subverting the law. If he tells them to follow the law and stone her, then the religious authorities can turn Jesus over to the civil authorities for inciting the crowd since the Jews could not inflict capital punishment on anyone themselves for any crime.

The Mosaic Law stated that such a crime was to be punished by stoning. If Jesus tells the crowd to let her go, then the authorities will say that he is subverting the law. If he tells them to follow the law and stone her, then the religious authorities can turn Jesus over to the civil authorities for inciting the crowd since the Jews could not inflict capital punishment on anyone themselves for any crime.

Next there is a rather dramatic pause, one that has baffled scholars as to what Jesus was writing on the ground. One theory, one which I very much like, says that the Lord was writing the sins of the woman’s would-be executioners on the ground in front of them. This theory is set forth because the normal Greek verb for “to write” is graphein; here, the Greek verb used is katagraphein which can mean “to write a charge against.” Whatever the Lord was doing in that moment is ultimately inconsequential because then he eloquently turns the tables on his would-be trappers. Reminding the crowd that the one who seeks to pass judgment is also liable to judgment, one by one they drop their stones and walk away.

The Gospel then leaves us with only the Lord and the woman, but to only focus on the Lord’s dispersing of the crowd and to not pay attention to the exchange that follows between the two would be a mistake. It would also be a mistake to underplay what the Lord says to her. The Lord Jesus extends his mercy to the woman, stating that he does not condemn her, but he also calls her to conversion: Go, and from now on do not sin anymore. Here we see the beautiful interplay between justice and mercy. Mercy is extended to this woman, but, with it, her conversion is commanded in justice. It is the same for us as well.

God does not dismiss our sins. He forgives us our sins with the understanding that we are to change our lives and avoid sin in the future.

Interestingly, this section of John’s Gospel was edited out for a time in the first few centuries of the Church’s life. St. Augustine states that this was done by certain Scripture scribes because it was a scandal to some in the early Church; a scandal that Jesus might seem to be “too light” on a sin as grievous as adultery. To the contrary of that ancient view of some, this story should be well-known to us because it reminds us first that, no matter how great our sinfulness may be, God’s love and mercy is greater. Second, as gracious as God’s forgiveness is, we should never be presumptuous of it, but accept it with humble gratitude and a firm resolve to change our lives. Finally, we must remember that ultimately there is one judge and no of us is he, and, in the end, we will all be in need of his mercy.

Father Christopher House is the Rector of the Cathedral and serves in various roles within the diocesan curia, namely Chancellor and Vicar Judicial.

4 Ways Lent Can (Still) Change You

Like the dark smudge on your forehead, Lent is something that has already disappeared for many in today’s stressful world. However, observing Lent can alter our perceptions and how we view the world can be greatly transformed. So, while there’s still time during this holy season, all is not lost.

We can take a page from a Jewish rabbi on this. On Yom Kippur he gave out to each member of his congregation a small piece of paper. On one side of it was written: “It’s later than you think!” On the other side, it said, “It’s never too late!” What he was speaking about is a sense of mindful prayerfulness — being in the now with our eyes wide open to the presence of God in so many different and wondrous ways. And, fortunately, this Lent, we still have time if we take it now. So, why not reflect on the following four ways Lent can change you?

-

Remember the ashes

The message of “from dust to dust we shall return” is not really a downer — it is reality. When we remember that we are mortal, impermanence can help us appreciate our lives even more. The ashes teach us to be more grateful for the people and things in our lives that are already there. Even though the ashes are physically gone, remember what they symbolize and you will live differently knowing this day can be your last.

-

Recognize that sacrifice is truly an act of beneficial simplicity

When we give things or activities up during Lent, it is not simply an act of self-denial, although it is good to postpone gratification at times. Instead, through the simplicity practiced in Lent, making our needs and consumption smaller, we can gain a greater appreciation of what is in our lives. Secular society would have us think we need more, but when we have it, we need even more. It also would have us think we need different but once we have it, it is the same. And, secular society would have us think we need perfect but there is no such thing or person but God. Lent helps us make our world smaller so our perception of all that is so good in it now becomes keener.

-

Lent gives us the opportunity to be compassionate in new ways

Almsgiving, which is one of the hallmarks of Lent, doesn’t involve simply giving money — although, once again, that is good too. It is giving of ourselves to others in our family, circle of friends, and at our workplace in a very different way. Namely, with a true sense of mitzvah, expecting nothing in return — not a smile, not a thank you, not an iota of appreciation. Learning this type of complete gift-giving of ourselves has a true platform in Lent under the banner of “almsgiving.”

-

Prayer gets a fresh start

By putting ourselves in the presence of God in the morning as we reflect on these four ways, we can allow Lent to be a time of change for us. The prayer life we always promised ourselves we would start or strengthen comes to life — maybe for the first time in a long while. We know that, along with fasting and almsgiving, prayer is the third and most important part of a Lenten practice, but after Ash Wednesday it usually falls by the wayside until we are abruptly awakened to the need for it during Holy Week. If we take a couple of minutes in the morning (remember, regularity rather than length of prayer is what’s important) to quiet ourselves before we get out of bed, maybe in the shower, or during our ride to work, we can begin a new prayer life regimen.

When God’s will and our will intersect, we become free, more whole, and life changes for the better — no matter what darkness we may be facing at the moment. And so, while some of Lent is still before us, let’s remember that “it’s later than you think” and “it’s never too late” if we turn to God now with a sense of spiritual intrigue as to how God is walking with us through life.

Dr. Robert J. Wicks is a clinical psychologist on the faculty of Loyola University Maryland. He has authored more than 50 books, the latest of which is Perspective: The Calm within the Storm.

Five Features of Faith

In our efforts to evangelize and proclaim the Gospel, it is good to keep our focus and prayer on the goal of our work—that others will come to faith in Christ and enjoy a personal relationship with him. This intrinsic connection between faith born from evangelization begins with Jesus himself in Mark’s Gospel where his first words are: “The time has come and the kingdom of God is at hand. Repent and believe the Good News!” (1:15). For St. John in his Gospel, his entire life of preaching and writing about Christ has been at the service of faith in him: “These things have been written so that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God and that through your faith in him you may have life” (20:30). So what then does this faith look like? What kind of faith do we hope to be born from our efforts to evangelize?

In our efforts to evangelize and proclaim the Gospel, it is good to keep our focus and prayer on the goal of our work—that others will come to faith in Christ and enjoy a personal relationship with him. This intrinsic connection between faith born from evangelization begins with Jesus himself in Mark’s Gospel where his first words are: “The time has come and the kingdom of God is at hand. Repent and believe the Good News!” (1:15). For St. John in his Gospel, his entire life of preaching and writing about Christ has been at the service of faith in him: “These things have been written so that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God and that through your faith in him you may have life” (20:30). So what then does this faith look like? What kind of faith do we hope to be born from our efforts to evangelize?

A Faith Born from Above.

In the fourth Gospel, Jesus reminds us that “no one can come to me unless the Father draws them” (John 6:44). Faith then is a gift from God born of hearing his Word and seeing it in action (cf. Rom. 10:17). Faith is not our own opinion or achievement. We cannot come to it by our own efforts. Faith does not arrive to us through one single argument or even a series of converging signs. Even when these signs are in place, it takes the gift of the Holy Spirit for us to finally “get it” and to assent to faith with our whole being. This is because the love of God engages the entire human being with all of his or her physical, psychological, and spiritual powers. This is what happened in the case of Lee Strobel as he tells his story in The Case for Christ in the movie based on the book of the same name. He set out to debunk his wife’s faith and gathered all the evidence he could find to prove his case. But while the evidence moved him in the direction of faith, it was the love of his wife and her prayers that finally clinched his assent.

A Faith that Grows. We often think of faith as something we have or we don’t have. I believe or I don’t believe and those are the only two possibilities. We also can think of faith as something that remains static and doesn’t grow. The truth is that faith can be born or reborn in us at any time, just like it was in the people who encountered Christ in the Gospels. For those who believe, there is an organic quality to faith that we recognize over time. Faith lives and grows. In the Gospels, Jesus often likens the gift of faith to a mustard seed (cf. Matt. 17:20). It begins small but can grow to such a degree that others benefit from it, like birds in the branches of a tree that began its life as a seed. Our faith in Christ is something alive and active. It prompts us to think in new ways, to act differently, and to understand God in bigger terms, beyond the image of him we already have. Faith also takes us beyond our comfort zones, moves us closer to those on the margins, and grounds our faith in the service of truth and charity.

This demands a necessary openness on our part to allow our faith to grow, to be affirmed and to be challenged when necessary. So when it comes to the big questions of our time, we should not be afraid to engage our faith with the confidence that the Holy Spirit gives us. The Gospel message entrusted to us bears within itself the truth that sets humanity free and sets us on course for a better life.

While this task of engaging with the big questions of the world can be difficult and even dangerous, it affords us the opportunity for our faith to be tested and to grow. It is like a muscle of our bodies that grows stronger when it is used and made to work. So far from being something static, our faith is something that progressively changes us to become more Christ-like and sends us on mission in his name. There is a dynamism in faith that invites us to a meta-noia or “going beyond the mind we have.” It opens us to new horizons and to see all things with new eyes.

A Faith that Draws Us into Relationship.

Faith is often exclusively associated with religion. So we might hear someone say: “Yes, I have faith, I believe in God”; or, “No, I don’t have faith, I am an atheist.” This is inaccurate because it assumes that only religious people have faith while nonreligious people don’t. The truth is that faith is much more part of everyday life than we realize. As Bishop Barron has often pointed out, if a young man is in a relationship with a girl, he can collect all the data he wants about her, but until she speaks to him, the relationship can never get off the ground. Only when the two parties speak to one another can the trust begin to grow. And if the relationship grows to the point of them wanting to marry, then their decision is still based on faith and trust. By getting married, both put their faith in one another and nourish that trust afterwards as husband and wife.

So it is with God. God has spoken first through his creation and through the history of a people he loved. In the words of St. John: “God loved us first” (1 John 4:19). As Christians we see this love offered to us through the person of Jesus Christ who came to reveal God to us. Faith then is our “Yes” that accepts the truth of what God has spoken and the love for us that he has revealed. Faith is a “Yes” to a “Yes.” It is our “Yes” to God’s “Yes” that comes first. This is the basis of a relationship that unites us to God.

A Faith in Christ Jesus Our Lord.

Throughout the Gospels, Jesus reveals a God who desires a personal relationship with each of us. Through faith and trust we are invited to know him and be known by him, to be loved by him and to love him in return.

Throughout the Gospels, Jesus invites us to faith in him: “Do not let your hearts be troubled. Trust in God still and trust in me” (John 14:1); “I am the resurrection and the life. The one who believes in me will never die” (John 11:25-26). What an extraordinary claim for anyone to make! There are only two possible responses to this invitation to faith by Jesus. One is to reject him out of hand as a narcissistic madman, and the other is to do exactly what he asks us to do and come to believe in him and who he claims to be. There is no middle ground.

The more we contemplate the life of Christ—his goodness, truth, and beauty—the easier it is to believe in him. First, his goodness —his mercy, his compassion, his patience, his understanding, and his love. He spent his whole life doing good for everyone, and his love gave birth to faith in him. His truth—before Pilate he said that he had come for this, was born for this, to bear witness to the truth, and all who are on the side of truth listen to his voice. Without truth, humanity caves in on itself in deception and fear. His beauty—the life of Jesus was beautiful and radiant with light as revealed at his Transfiguration. And all who are united with him in Spirit radiate that same light and exude the fragrance of his charity. This is why he asks us to be light to the world (Matt. 5:14) and carry the light of his presence to all we meet.

A Faith to Be Shared.

The gift of faith is not given for ourselves. It is given to be shared. The joy of the Gospel leads us to be people of mission in all kinds of ways. We want others to know God and we desire to lead others to faith in him. We want his kingdom of peace and justice to flourish, and so pray for it and work for it. In this spirit, Pope Francis urges us to “go forth to offer everyone the life of Jesus Christ” (The Joy of the Gospel, 49). Our act of believing must allow the joy of faith to shine through in lives that are centered on the Lord and united to others in community. And it is with others in the family of the Church that our faith is nourished and strengthened to carry it forth to all in Jesus’ name.

For us dedicated to evangelization, the haunting words of Jesus are never far from our hearts: “When the Son of Man returns, will he find any faith on earth?” (Luke 18:8). Evangelization is not an end in itself but is at the service of faith. This article has described five features of that faith: that it is a gift from God that grows, that draws us into relationship, that centers on Jesus Christ, and that leads us to give ourselves away in loving service and mission. May the quality of our own faith be marked by these features so that we can share it confidently and effectively with a skeptical world.

Fr. Billy Swan is a priest of the Diocese of Ferns, Ireland. He holds a degree in chemistry and worked for a number of years for a pharmaceutical company before entering seminary. Ordained in 1998, he served for four years as an associate pastor before further studies in Rome where he was awarded a Licentiate and Doctorate in Systematic Theology from the Gregorian University. He served for four years as the Director of Seminary Formation at the Pontifical Irish College, Rome. He is currently based at St Aidan’s Cathedral, Enniscorthy, Co. Wexford.