I’m not big on jewelry, but one thing you might notice about me is that I always wear a crucifix around my neck. It is not a cross, but a crucifix. There is a reason for that. In fact, I want to share three reasons why I wear a crucifix.

I’m not big on jewelry, but one thing you might notice about me is that I always wear a crucifix around my neck. It is not a cross, but a crucifix. There is a reason for that. In fact, I want to share three reasons why I wear a crucifix.

Reason #1 — Remembrance: To Remember What True Love Looks Like

The crucifix is different than the cross. The cross is the instrument of torture with which Jesus was murdered, a particular favorite of the Roman Empire. The cross is the altar on which the Son of Man offered himself as an eternal sacrifice for the forgiveness of our sins. The cross is the new tree of life. The cross is significant, but only because of the time Jesus spent hanging from it.

For some people the cross is scandalous. It is something they hold to be in the past. As a Catholic I believe that the sacrifice of Jesus on the cross is eternal, and made ever-present at every Mass held everyday in every country around the world. “But we proclaim Christ crucified, a stumbling block for Jews and foolishness for Gentiles, but to those who are called, Jews and Greeks alike, Christ the power of God and the wisdom of God” (1 Corinthians 1:23-24).

Don’t get me wrong. I know Jesus is not on the cross. He is not dead. He is risen. In fact: “A Catholic is one who believes that this Jesus remains alive, active, and accessible in and through His Church.” (Archbishop Timothy Cardinal Dolan)

Jesus on the cross is what matters. It is the ultimate act of God’s love for us. To gaze upon the crucifix, for me, is to look upon love in its most perfect expression. In the busyness of my daily life I need to be reminded of that, and reminded often. The crucifix around my neck serves as a reminder of God’s love for the world, but particularly God’s love for me.

Reason #2 — Inspiration: To Inspire Me to Take Up My Cross Daily

The crucifix might be thought of as a gruesome sight. However, for me it is inspiring. To see Jesus on the cross is a reminder of the challenge he made to his disciples—the challenge he makes to me. “If anyone wishes to come after me, he must deny himself take up his cross daily and follow me” (Luke 9:23).

It’s not a suggestion or a good idea; it is the condition of discipleship. To be a disciple is to make your life about this challenge. And believe you me, it is a challenge. This is why I need to be inspired. This is why I like to contemplate the image of Christ crucified: not because I enjoy seeing him broken and bloody, but because I know those are the footsteps in which I must follow.

As a Christian I know I am called to be a martyr—a witness. Who I am in life and in death must bear witness to Christ. Whether that means I will literally lay down my life for him, I cannot be certain. But come what may, the challenge made to we disciples is just that: to accept the pain and suffering that can and will come our way because of our free decision to follow Jesus.

“Blessed are they who are persecuted for the sake of righteousness, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 5:10). Seeing Jesus on the cross is an inspirational example that I am called to follow, and this is another reason for the crucifix around my neck.

Reason #3 — Accountability: So Others Will Hold Me Accountable as a Christian

The last reason I wear a crucifix is for accountability. It is not jewelry. It is not meant to be flashy. But I do want others to see it. It’s not because I want them to think I am super holy. (Although I should be striving for holiness; after all, that is the call we share as Christians.) I wear a crucifix so that others may know that I am a Christian and hold me accountable to that claim. For it is one thing to tell people you are a Christian and another to show them that you are. I want to be treated differently because of my faith. I want people to know that I live my life differently than most. When they know this, they will expect me to. And if I don’t, then I need to be called out for it.

Accountability is important. Fraternal correction is essential. We shouldn’t be able to parade around claiming to be new creations in Christ, but living lives that don’t follow suit. And the crucifix I wear is the perfect symbol of my faith that tells all those who encounter me that I am a Christian and take my faith seriously.

I can’t wear the crucifix and then deny my faith. It would cause scandal. People would notice. So it is the perfect way to invite others to challenge me to live my faith.

There may be other methods of achieving each of these three things shared here, but for me the crucifix is the best. If you wear a crucifix but don’t know why, then I hope these reflections have served to help you understand this practice on a deeper level. If you aren’t Catholic and always wondered why the crucifix is held in such high esteem among Catholics, then hopefully this explains it.

May the sacrifice of Christ on the cross bring the power of God’s love and mercy into each of our lives, that we may “proclaim Christ crucified” (1 Corinthians 1:23) and “make disciples of all nations” (Matthew 28:19).

A convert to Catholicism, Ricky Jones came into the Church in 2008 and has served as a catechist and parish leader. He blogs about faith at LeadersThatFollow.com. He is the author of Seven Lessons in Leading People to Life Change, a practical guide for living your faith, leading people into relationship with God, and building up the Church.

Almsgiving is more than just allocating surplus funds to a charitable organization or cause. More is expected of us than that! Think of almsgiving as acts of generosity that enable the performance of the corporal and spiritual works of mercy. It is through the corporal and spiritual works of mercy that we show ourselves to be faithful, rather than accidental, disciples.

Almsgiving is more than just allocating surplus funds to a charitable organization or cause. More is expected of us than that! Think of almsgiving as acts of generosity that enable the performance of the corporal and spiritual works of mercy. It is through the corporal and spiritual works of mercy that we show ourselves to be faithful, rather than accidental, disciples. The first reading from the Book of Genesis and the passage from the Gospel of Mark that are both given to us for this First Sunday of Lent may appear to have no relationship to each other but that is not the case. As we begin this holy season, one of the themes that is presented to us is the call for the renewal of baptismal grace in each one of us. Immediately in the first reading we are given an allusion to something great that is to come: baptism.

The first reading from the Book of Genesis and the passage from the Gospel of Mark that are both given to us for this First Sunday of Lent may appear to have no relationship to each other but that is not the case. As we begin this holy season, one of the themes that is presented to us is the call for the renewal of baptismal grace in each one of us. Immediately in the first reading we are given an allusion to something great that is to come: baptism. Bishop David L. Ricken of Green Bay, Wisconsin, former chairman of the Committee on Evangelization and Catechesi s of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB), offers “10 Things to Remember for Lent”:

Bishop David L. Ricken of Green Bay, Wisconsin, former chairman of the Committee on Evangelization and Catechesi s of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB), offers “10 Things to Remember for Lent”:

We’ve probably all received an unexpected gift or act of love. Perhaps this past Christmas someone we didn’t know very well— and from whom we didn’t expect anything—brought us a gift or wrote us a nice card. Since we didn’t expect it, we may feel uniquely loved and valued. We’re touched by the act, possibly more so than gifts by our loved ones, which we expect on some level. The urge breaches to do something nice for that person, to offer them something tangible as well—to remit payment for the free, unexpected act of kindness. Since they did something nice for me, surely I must do something similar in return.

We’ve probably all received an unexpected gift or act of love. Perhaps this past Christmas someone we didn’t know very well— and from whom we didn’t expect anything—brought us a gift or wrote us a nice card. Since we didn’t expect it, we may feel uniquely loved and valued. We’re touched by the act, possibly more so than gifts by our loved ones, which we expect on some level. The urge breaches to do something nice for that person, to offer them something tangible as well—to remit payment for the free, unexpected act of kindness. Since they did something nice for me, surely I must do something similar in return. We do not know who wrote the Book of Job, but it was likely written between the 7th and 5th centuries BC. The book centers on numerous tragic events that happen to Job, who himself is a good and holy man, and these events are the source of great suffering for him. The book contains varying discourses from Job, his neighbors, and finally from God. In the first reading for this Fifth Sunday in Ordinary Time, we hear of Job’s frustration, sorrow, and even anger at the events that have happened to him and the direction that his life has taken. Towards the end of the book, God speaks to Job in a wonderful, vivid discourse, reminding Job, and us, that God’s ways are far beyond us. At the end of the book, God makes all things right for Job, yet there is one thing in reading the Book of Job that you will find lacking: an answer to the question of why do bad things happen to good people.

We do not know who wrote the Book of Job, but it was likely written between the 7th and 5th centuries BC. The book centers on numerous tragic events that happen to Job, who himself is a good and holy man, and these events are the source of great suffering for him. The book contains varying discourses from Job, his neighbors, and finally from God. In the first reading for this Fifth Sunday in Ordinary Time, we hear of Job’s frustration, sorrow, and even anger at the events that have happened to him and the direction that his life has taken. Towards the end of the book, God speaks to Job in a wonderful, vivid discourse, reminding Job, and us, that God’s ways are far beyond us. At the end of the book, God makes all things right for Job, yet there is one thing in reading the Book of Job that you will find lacking: an answer to the question of why do bad things happen to good people. As cited in the Catechism (No. 2043), the Precepts of the Church maintain that each person has the duty to support the material needs of the Church. Of course a person fulfills this obligation according to his abilities. The Code of Canon Law also states, “The Christian faithful are obliged to assist with the needs of the Church so that the Church has what is necessary for divine worship for apostolic works and works of charity end for the decent sustenance of ministers” (No. 222). However, the Church does not mandate a “tithe” as such of any percentage of income or other resource.

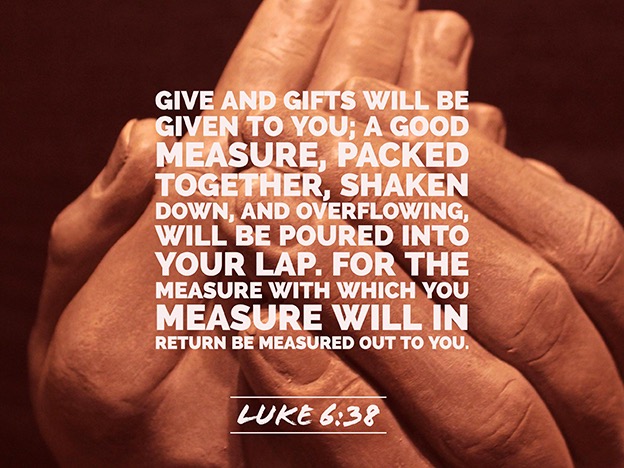

As cited in the Catechism (No. 2043), the Precepts of the Church maintain that each person has the duty to support the material needs of the Church. Of course a person fulfills this obligation according to his abilities. The Code of Canon Law also states, “The Christian faithful are obliged to assist with the needs of the Church so that the Church has what is necessary for divine worship for apostolic works and works of charity end for the decent sustenance of ministers” (No. 222). However, the Church does not mandate a “tithe” as such of any percentage of income or other resource. The Torah laws prescribe the offering of tithes A person offered to God, or “tithed,” one-tenth of the harvest of grain of the fields or the produce of fruit of the trees, one-tenth of new pressed wine and oil, and every tends firstborn animal of herd or flock (Leviticus 23 30-33. Deuteronomy 12:17. 14:22-29). Such tithing recognized that God had graciously bestowed these blessings upon man, and man in return offered a thanksgiving sacrifice of one-tenth of the “first fruits.”

The Torah laws prescribe the offering of tithes A person offered to God, or “tithed,” one-tenth of the harvest of grain of the fields or the produce of fruit of the trees, one-tenth of new pressed wine and oil, and every tends firstborn animal of herd or flock (Leviticus 23 30-33. Deuteronomy 12:17. 14:22-29). Such tithing recognized that God had graciously bestowed these blessings upon man, and man in return offered a thanksgiving sacrifice of one-tenth of the “first fruits.” Although we may not have a rule of tithing, we do have the duty to support the needs of the Church, whether at the international, diocesan or parish level. Each of us should evaluate what we do “give back to God” through our support of the Church and charitable organization. For example, we should ask, “Do I give to God each week at least what I spend on entertainment, such as movies? Do I give to God at least one hour’s worth of my 40 hour pay check?” St. Paul in his Second Letter to the Corinthians (8:1-7) praised the generosity of the faithful in Macedonia: “In the midst of severe trial their overflowing joy and deep poverty have produced an abundant generosity According to their means — indeed I can testify even beyond their means — and voluntarily, they begged us insistently for the favor of sharing in this service to members of the church. “Each of us should be more of a “tither” than a “tipper” in returning a portion of our bounty back to God.

Although we may not have a rule of tithing, we do have the duty to support the needs of the Church, whether at the international, diocesan or parish level. Each of us should evaluate what we do “give back to God” through our support of the Church and charitable organization. For example, we should ask, “Do I give to God each week at least what I spend on entertainment, such as movies? Do I give to God at least one hour’s worth of my 40 hour pay check?” St. Paul in his Second Letter to the Corinthians (8:1-7) praised the generosity of the faithful in Macedonia: “In the midst of severe trial their overflowing joy and deep poverty have produced an abundant generosity According to their means — indeed I can testify even beyond their means — and voluntarily, they begged us insistently for the favor of sharing in this service to members of the church. “Each of us should be more of a “tither” than a “tipper” in returning a portion of our bounty back to God. “I just want you to be happy.”

“I just want you to be happy.” Climbing the levels of happiness requires us to slowly eschew our own faults and failings, and to recognize that perhaps what we thought made us happy is only the first step. This ladder can often appear as a difficult climb ahead, so when we use the words, “I just want you to be happy,” we need to be viscerally aware of the fact that the happiness we are presenting is going to hurt, in the sense that our egos will be tested, but also restore in the loving embrace of Christ’s divine life which can best be found in the sublime beatitudo.

Climbing the levels of happiness requires us to slowly eschew our own faults and failings, and to recognize that perhaps what we thought made us happy is only the first step. This ladder can often appear as a difficult climb ahead, so when we use the words, “I just want you to be happy,” we need to be viscerally aware of the fact that the happiness we are presenting is going to hurt, in the sense that our egos will be tested, but also restore in the loving embrace of Christ’s divine life which can best be found in the sublime beatitudo.